21 December 2020 by bobhud

“Hail, daughter Genovefa!”: Imitatio Mariae in the Musée de Cluny’s 14th-Century Tableau Reliquary of St. Genevieve

Meredith Hanna Noorda

Brigham Young University

Ornamented with translucent, jewel-toned enamelwork and engraved with delicate organic motifs, the Tableau Reliquary of St. Genevieve held at the Musée de Cluny showcases fourteenth-century mastery of goldsmithing and the importance of relics in the medieval French Church (see Figure 1 below). This pendant reliquary contained more than 50 small relics, including fragments of the True Cross and of St. Genevieve, the latter of whom is represented on the front panel. In this scene, depicting one of the central stories of her legend, St. Genevieve is shown holding a candle, which has been relighted by an angel after having been put out by a demon. With downcast eyes, blonde hair, and a serpentine, heavily draped body, the figure of St. Genevieve is a courtly feminine ideal.[1]

However, this little-studied work is notable not simply for its workmanship and its purported royal provenance (it was said to have been given from Louis XIV to his mistress Madame de Maintenon) (“Tableau-Reliquaire”). It is indicative of the rise of St. Genevieve in Gothic Parisian religious and political life, and, as this article argues, can be read as representative of the resulting theological association between St. Genevieve—the Patron Saint of Paris—and the Virgin Mary in discourse and religious practice. In both of their works on Genevevian devotion, Moshe Sluhvosky and Brianna M. Gustafson have touched on the close and seemingly fraught relationship between these two female saints, manifested in ecclesiastical rhetoric and royal patronage. However, analyses of visual examples from the period that may suggest comparisons or hierarchies between these two holy women have been largely neglected in these works.

Figure 1. Tableau-Reliquaire de Sainte Geneviève, 1380–90, 8.1 x 6.6 cm, Paris, Musée de Cluny

Pseudo-Dionysus, whose writings would prove enormously influential in the development of the Gothic style, wrote that “the entire world of the senses in all its variety reflects the world of the spirit. Contemplation of the former serves as a means to elevate ourselves towards the latter” (cited in Edwards 162). In studying the physical aspects of the reliquary, as well as in considering how it would have been handled by a late medieval devotee, a deeper understanding of the allusions and the sacred connotations of the object can be discovered; likewise, it can allow us to comprehend how the Virgin’s essence permeates the reliquary, without being figuratively represented. Through the lens of the medieval practice of imitatio, this article will explain how the Tableau Reliquary employs materials and iconography to depict St. Genevieve as a devoted imitatio mariae, while asserting that the saint’s holiness makes her a similarly venerable holy woman.

While Paris’ reputation as a center for scholarship and culture was developing in the Middle Ages, the cult of St. Genevieve had become prominent, venerated to a level of intensity and devotion reserved for only the highest of holy persons. According to her vita, St. Genevieve, or Genovefa in Latin, was born to German or Frankish parents in 420. Her piety and grace had been noted since her early childhood, and an encounter with St. Germain of Auxerre at the age of seven confirmed her commitment to life-long consecration as a bride of Christ. Taking the veil at 15, she left her hometown of Nanterre when her parents died, and moved to Paris to be raised by her godmother. Her distinguishing miracle occurred in 451, when Attila the Hun approached Paris and many fled the city. Genevieve prophesied that Paris would not be harmed and gathered the city’s matrons to pray and fast. Though Genevieve’s plan and prophecy proved unpopular, divine interventions and miracles persuaded the Parisians to believe her and the Huns rerouted. The subsequent years were rich in healings and service on behalf of the people of Paris. She organized a mission to bring food from the countryside to Paris during a famine, participated in the planning of a chapel dedicated to Saint Denis, and worked with Clothilde, Queen of the Franks, to convert the Frankish king Clovis to Christianity in 496. Genevieve died soon after, c. 500, her tomb quickly becoming a site of veneration (Sluhvosky 11–12).

Étienne de Tournai, Abbot of the Abbacy of St. Genevieve, reflected the supreme importance of the saint to twelfth-century Parisians in his feast day remarks, stating the following:

On this day, the presence of the body of our virgin makes the joy of our city both ordinary and remarkable, for though her memory is present in other places during the benediction, here her presence resides in passion and gladness; in other places her feast day is celebrated annually, but here it is observed daily and without end. (cited in Gustafson §1)

“Ordinary” in its regular occurrence, and “remarkable” in its significance, devotion to St. Genevieve became characteristic of Parisians until the Revolution. As the Patron Saint of Paris, she had a myriad of associations: bread, food, water, the various confraternities and women’s religious groups that were formed in her name, along with the most recognizable as protector of Paris (Sluhvosky 32–63). Her image and legends became sacred to both Church and political functions, St. Genevieve being an embodiment of both the French church and the French state.

St. Genevieve’s political favor is seen in the royal patronage of her abbey, which housed her jewel-encrusted body reliquary. Located on the Left Bank of Paris, this expansive complex was placed under the direct control of the Capetian monarchs by King Robert the Pious, who himself gifted it several more properties. Pope Pascal entitled the Abbot of St. Genevieve in 1107 to nullo mediante, meaning that the abbot and his abbacy were free from episcopal interference and could personally collect all taxes for the properties within the abbacy. This mandate also allowed the abbot to function as a bishop, with the ability to perform marriages and deliver extreme unction (Gustafson §3). As a further show of the abbey’s Parisian sovereignty, prospective bishops of Paris had to swear on the Bible to never violate the abbey’s privileges before assuming their see (Sluhvosky 82). St. Genevieve’s monarch-supported prominence would be felt throughout Paris on her feast days and processions, which often entailed walking from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame to the Abbey of St. Genevieve (Sluhvosky 77).

Along with Genevieve’s rise in popularity in the Middle Ages, European Christianity was turning towards the holiest of female Christian figures, and a truly universal saint, the Virgin Mary. Like Genevieve, the Virgin was associated with the French state, and represented a maternal, feminine gentleness that so characterized both the intellectual currents of the day and popular desires for an abundantly merciful intercessor (Saupe §1, 20, 24). Theologically, the Virgin’s life was increasingly seen as a mirror for Christ’s, with a possible immaculate conception and resurrection of her own (Mooney 68). The Gothic age flourished with the cult of the Virgin, with many Gothic ecclesiastical structures in France dedicated to Our Lady.

In Paris, Genevieve would become tied to the Abbey of St. Genevieve, and the Virgin Mary with the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, whose respective abbot and bishop, as previously stated, had almost the same powers. The resulting conflict was reflected in the incident of the 1129–30 ergotism epidemic, where the sick touched the reliquary of St. Genevieve, situated at that time in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, and were healed. The canon of St. Genevieve said that all credit was due to St. Genevieve and a counterpart from Notre-Dame maintained that the Virgin had also interceded and was primarily responsible for the healings; exempt from the debate, medieval hymns attributed the healings to both, recognizing both women as “co-patrons of Paris” (Sluhvosky 23). The miracle would be celebrated by the Diocese of Paris every November, following the account of the epidemic as dictated by the Abbey of St. Genevieve, and thus emphasizing the Parisian saint’s miraculous role and her holy relevance to the city (Gustafson §8). As Gustafson writes of this event and subsequent ecclesiastical remarks: “In a time of increased devotion to the virgin mother of Christ, the canons argued that, though Mary was notre dame in a universal sense, Geneviève was Paris’ true lady and mother” (§5).

While Mary was, of course, lower in the divine hierarchies than Christ, imitation of her—classified as Imitatio Mariae—was a pursuit encouraged by many medieval theologians. Imitatio was a general principle that entailed modeling one’s life after that of a holy person—be it Christ, Mary, or a saint; this could include forsaking wealth, taking a vow of chastity, giving aid to the poor. Marielle Lamy has identified two ways Mary was employed as a model for imitatio: as a model for the religious life, and as a model for devotion to Christ (Lamy 63).

The principals of imitatio may been seen in texts, where hagiographies compare the saint in question to another holy person. One example of textual Imitatio Mariae is seen in writings about St. Clare of Assisi shortly after her death, when witnesses are reported as saying that no woman had been as holy as Clare save the Virgin. As time progressed, writers began to view Clare as a near-equal partner to Mary in righteousness:

The comparison of Clare and Mary […] is memorable because Medieval interpreters writing after the Process continue to juxtapose Clare and Mary, but instead of alluding to Clare’s inferiority (however slight) to the Virgin, they begin to describe the two in more mutual terms, describing Mary as Clare’s model, and Clare as Mary’s imitator. (Mooney 59)

Viewing St. Clare as an Imitatio Mariae is dubious because the saint’s own writings emphasize Christ as the central object of imitation; Mary is presented as a model for imitatio less frequently, and only inasmuch as she represents spiritual motherhood and closeness to Christ (Mooney 66–67). For Mooney, this seems to be an instance of male writers likening holy females to each other largely due to the simple fact of their gender (Mooney 71). Even with the historical incongruities at play in Clare’s hagiographies, however, the more mutual terms that were used to describe Clare and the Virgin are evident in comparisons of St. Genevieve and the Virgin, and suggest that laudatory writings of Genevieve that place her near Mary’s exalted position may not have been as presumptuous and blasphemous as they may seem to contemporary readers. That the Abbot of St. Genevieve’s comments were propagandistic at the expense of the Virgin seems clear, but the general sentiment, that a local saint could be on equal footing with Mary, Mother of Christ, has precedent in writings about Clare of Assisi. This give a basis for why St. Genevieve’s image would be on a finely crafted, undoubtedly costly reliquary, rendered in materials associated with the Virgin.

St. Genevieve’s Parisian prominence and her own worthiness as a model for imitatio are demonstrated in the wearability of the reliquary. Rendered in gold in exquisite craftsmanship, the color and material are integral to an aspect of St. Genevieve’s legend and a pendant that she was said to wear in life. In her meeting with St. Germain of Auxerre when she was a child, he consecrated her to life of piety and offered her a copper pendant, telling her to wear it and no other decoration and jewelry. The following is an excerpt from her vita detailing the event:

I don’t know what celestial things Germanus perceived in her, but he said: “Hail, daughter Genovefa! Do you remember what you promised me yesterday concerning your virginity?” To which Genovefa replied: “I remember, holy father, what I promised to God and to you. God helping me, I hope to keep my mind chaste and my body untainted to the end.” Then Saint Germanus plucked a copper coin bearing the sign of the cross from the ground, where by God’s favor it had fallen, and gave it to her as a great gift. Her said to her, “Have this coin pierced, and wear it always hanging about your neck as a reminder of me; never suffer your neck or fingers to be burdened down by any other metal, neither gold nor silver, nor pearl studded ornament. For, if your mind is preoccupied with trivial, worldly adornment, you will be shorn of eternal and celestial ornaments” (cited in McNamara et al. 21).

The Tableau Reliquary—a small, almost entirely metallic pendant—mimics this first mark of St. Genevieve’s life of piety, a token given to her by a saint who saluted her auspiciously with “Hail,” mirroring the Ave Maria. That the reliquary would hold a piece of the True Cross is additionally significant, as her bronze pendant was marked with a cross, and the True Cross is directly tied with the Gothic French monarchy and their history of relic acquisition. While St. Germain’s admonition excludes the wearing of precious materials, the reliquary may be seen as showing St. Genevieve’s divinity; her memory is now worthy of precious materials as they reflect the preciousness of her life and spirit, the “adornment” of righteousness.

A pendant reliquary had several potential functions: suspended above an altar, worn around the neck in liturgical ceremonies, or handled personally in private devotion. “Movement, and the experience of seeing [the relic] from varying angles and positions was essential to the function of the pendant reliquary as a medieval devotional and performative object,” writes Karen Overbey in her analysis of a Scottish pendant reliquary made c. 1200 (250–51). Thus the portability and the three-dimensional quality of the Tableau Reliquary was particularly important to a reliquary of St. Genevieve, as it could be worn in these parades and sacred processions. Public and communal manifestations of imitatio through processions and plays were considered to be the most effective in combining a biblical or holy past with the medieval present, a “mysticism of a historical event,” where participants and onlookers could enter into a spiritual event and draw “spiritual energy” from the experience (Nius 2). Even without the organized procession, the act of walking and moving with the sacred object through either a secular or sacred space calls to mind the experience of the sacred procession which worship of St. Genevieve is so characterized by. The Tableau Reliquary reflects this practice of mystically placing oneself in the place of, or alongside, a holy person, by assuming integral elements of dress that draw one closer to a mystical image of the person.

The other use of a pendant reliquary—to be suspended above an altar—may be seen as a reference to the hanging container of the host, known as a pyx, a common element of medieval churches. The practice of bringing the host to a specified location at the main altar was a medieval innovation, allowing the faithful to pray in front of it, presumably independently of the mass or as a part of the service. Commonly made in metal and often in the shape of a dove, the pyx would be locked with the host inside. After much debate throughout the Middle Ages transubstantiation was accepted in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as the official, accepted doctrine, wherein the substance of the host is changed to the body of Christ while retaining the same physical sensory shape of the wafer.[2] Belief as to the miraculous capabilities of the host itself had become common, and evolving medieval ritual reflected this fervent consideration of the host as not only an essential functional element but as an object of visual devotion. Priests developed the practice of holding the host over the heads and of displaying it with a monstrance during a procession to the altar, undoubtedly a result of this desire to behold the host as well as to show the omniscience of Christ and His sacrifice.

The Tableau Reliquary can be read as making several allusions to these hanging containers of the host, which themselves can be seen as reliquaries for the body of Christ. The Tableau Reliquary is made in gold, a color connected with the divine, sacred, royal, and the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is also connected to the form of the dove, a common figure for pyxses. Having made reference to the glories of God and Heaven through its material, it is thus fit to hold the body of a holy worshipper of Christ as the pyx holds the host. As a container, it holds these fragments of a precious body like the womb of Mary holding her unborn son in a pure, undefiled vessel. Recalling the spiritual knowledge she received and the miraculous events she witnessed and “kept in her heart” (Luke 2:19) Mary is depicted in the Bible as one who contains, and by containing, transforms; this concept is corroborated in medieval theological thought, where St. Francis of Assisi emphasized imitating Mary in her role as “Christ-carrier” (Mooney 66). The Tableau Reliquary itself is an imitation of the Virgin in its nature as a suspended, containing, divinely radiant object whose inherently precious exterior holds and protects a profoundly spiritual interior.

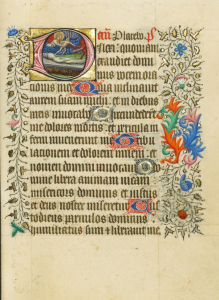

Figure 2. Master of Sir John Fastolf (French, active before about 1420–c. 1450), Initial D: An Angel and Devil Disputing the Soul of a Dead Man,

c. 1430–40, Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment; 12.1 x 9.2 cm (4 3/4 × 3 5/8 in.), Ms. 5 (84.ML.723), fol. 171, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 5, fol. 171

Pyxes were additionally used to transport the Blessed Sacrament to the sick and dying; this function adds resonance to the hagiographic scene at the front of the Tableau Reliquary. St. Genevieve was, as previously mentioned, known for the story of her candle, relit miraculously by an angel after having been put out by a devil. Medieval deathbed scenes frequently showcased a confrontation between devil and angel, the two fighting over a recently departed soul (see Figure 2 above). In the Tableau Reliquary, the emissaries from the lands of the righteous and wicked swoop into the frame from either side, mimicking these deathbed scenes, and situating St. Genevieve in the middle. With the reliquary’s similarities to a pyx—transportable, hanging, metal—it engages with death rites and judgement, places where the Virgin Mary had special relevance as an intercessor. St. Genevieve transposes herself into this context, becoming the visual intermediary between good and evil, and thus subtly inhabiting one of Mary’s roles.

The colors of the enamel details—purple, blue, green, yellow—can be read separately and collectively as allusions to the Virgin. St. Genevieve and the angel’s yellow hair reflects medieval views of holy virginal beauty, purple was an expensive dye, used for royalty and associated with martyrs, blue the Virgin’s own color (Philips 64). Together, they make St. Genevieve like the Virgin, “that one incomparable jewel,” multi-faceted and radiant in color (Durandus and Santo Victore 30). St. Genevieve is shown holding a book, almost certainly the Bible or another holy book as the scene depicted revolves around her ecclesiastical worship. In this she becomes like the Virgin, holding the Word as Christ and covering it with her purple shawl, drapery that called to mind the sacrifice of the Passion. The fourteenth century also marked the translation of St. Genevieve’s vita into the vernacular French, and so the book can be seen as St. Genevieve’s life in print, a continuation and repetition of the printed Word (Sluhvosky 24).

The enamel of the Tableau Reliquary is in bright, jewel-like colors that mimic those of stained glass, but they are juxtaposed with an abstract gold background, almost as if they were stained onto the object. The enamel itself can be seen as an extension of the iconographic allusions made in the reliquary, enamel being associated with glass, and glass associated with the towering windows of Gothic churches in the Virgin’s name. The medieval view of glass as it related to windows is reflected in a thirteenth-century text detailing the symbolism of every element of a church: “The glass windows in a church are the Holy Scriptures which expel the wind and the rain that is all things hurtful, but transmit the light of the true sun, that is, God, into the hearts of the faithful” (Durandus and Santo Victore 18). The clarity of glass and its crystalline appearance were integral elements of a common medieval analogy about the Immaculate Conception, which stated that like a beam of light passing through a window, Mary’s purity was such that the act of conceiving passed through without affecting her chastity. Mary was likewise compared to a mirror, with St. Ambrose writing, “Let, then, the life of Mary be as it were virginity itself, set forth in a likeness, from which, as from a mirror, the appearance of chastity and the form of virtue is reflected” (374–75). St. Genevieve, rendered in enamel and placed squarely in the middle of the shimmering reliquary, is thus the mirrored image of the Virgin and her attributes, suggesting purity, virginity, radiance, and other virtues that glass connoted to medieval Christians.

Likewise, the Tableau Reliquary was made of the same metals as an icon, a medium highly associated with Eastern images of the Mother and Child. Icons were thought to function like windows or mystical passageways to interact with the Divine, bringing the worshipper through “a series of transcendences which [culminate] in anagogic truth” (Edwards 162). The repeating rectangular shape of the Tableau Reliquary reinforces this concept, inviting the viewer to mystically enter deeper into the life and teachings of St. Genevieve. It also invites the viewer or worshipper to consider how Genevieve may be comparable to the Virgin, whose image typically dominates the iconic frame. Glass-like enamel furthers the iconic aspect of the reliquary, rendering the figures bright and colorful, but ultimately flat and two-dimensional, like those on an icon.

The pendant’s ten metal flowers suggest a number of Virginal references. Its rectangular shape and continuous frames may point to the allusion of the Virgin as the enclosed garden, as St. Genevieve is enclosed in a flowering space surrounded by red flowers, presumably roses. She and the Virgin Mary were themselves likened to roses, with Genevieve in her liturgy “likened to a rose whose odor is that of health and whose blossom ‘spreads its dew on the glory of the city’” (Gustafson §16). As a hanging devotional object, the reliquary has elements in common with rosaries, which the faithful were increasingly using in the Middle Ages to fortify their relationship with Mary. The metal flowers suggest the rosarium (“wreath” or “rose garden”) from which the “Rosary” takes its name. The number of roses—ten—may also be significant; though the number of beads on rosaries varied throughout the Middle Ages, the sixteenth century saw ten become the codified number of beads for each of the five sections. A reference to the rosary could invite a Parisian devotee to seek with greater diligence the mercy of St. Genevieve, believing that prayers directed to her would be responded to with power comparable to that of the Virgin; they might even be responded to with greater interest, since, as the Abbot of St. Genevieve argued, St. Genevieve was thought to have a more particular love for Paris than Mary (Gustafson §6). Through these shared symbols and references made through material, image, and form, the two become inextricably connected in the mind of the worshipper—the Virgin bringing St. Genevieve to a higher plane of intercession, St. Genevieve tying the Virgin closer to the city of Paris.

The Tableau Reliquary of St. Genevieve reflects the comparison that many ecclesiastical leaders of the fourteenth century made between the two most prominent female saints of Paris. In bringing together their particular allusions, an object was created that would deepen faith in both as it was used and admired. By approaching this little-studied work from a material standpoint, rich layers of meaning are discovered, demonstrating that theologians were conscious of craft and material signification. Conversely, it suggests that craftspeople were conscious of the impact materials could have on the spirituality of devotional objects. By representing St. Genevieve, and the Tableau Reliquary as a whole, in materials associated with the Virgin Mary, the patron saint is revealed to be an Imitatio Mariae; this, in St. Genevieve’s case, however, was not a wholly subservient position. St. Genevieve’s alignment with the Virgin—both textually and visually—shows how powerful her image and life were to medieval Paris, and, by extension, how powerful Paris became in those centuries. Genevieve herself is presented as a figure deserving of imitatio, a worthy co-protector of Paris alongside Mary.

Works Cited

Ambrose (Saint), “Concerning Virgins,” in The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, vol. 10, eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983), 374–75.

Durandus, Guilielmus, and Hugo de Sancto Victore, The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum: The Foundational Symbolism of the Early Church, its Structure, Decoration, Sacraments, and Vestments […] including The Mystical Mirror of the Church (Louisville: Fons Vitae, 2007).

Edwards, Robert. “Techniques of Transcendence in Medieval Drama.” Comparative Drama 8.2 (1974): 157–71.

Gustafson, Brianna M. “Miraculis Virgo: The Abbey of Sainte-Geneviève and the Cult of Geneviève in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries,” Journal of the Western Society for French History 38 (2010). (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/w/wsfh/0642292.0038.001/–miraculis-virgo-the-abbey-of-sainte-genevieve-and-the-cult?rgn=main;view=fulltext), accessed August 10, 2020.

Lamy, Mirielle. “Marie, modèle de vie chrétienne: quelques aspects de l’imitatio Mariae au Moyen Âge,” in Apprendre, produire, se conduire: Le modèle au Moyen Âge. (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2015), 63–78.

McNamara Jo Ann, John E. Halborg and E. Gordon Whattley, eds. and trans. Sainted Women of the Dark Ages (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1992).

Mooney, Catherine M., ed. Gendered Voices: Medieval Saints and Their Interpreters. (Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1999).

Njus, Jesse. “What Did It Mean to Act in the Middle Ages?: Elisabeth of Spalbeek and ‘Imitatio Christi’,” Theatre Journal 63.1 (2011): 1–21

Overbey, Karen. “Seeing through Stone: Materiality and Place in a Medieval Scottish Pendant Reliquary,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 65–66 (2014–15): 242–58.

Phillips, Kim M. “Beauty,” in Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia, ed. Margaret Schaus (New York: Routledge, 2006), 64–65.

Saupe, Karen, ed. “Introduction,” Middle English Marian Lyrics (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997). (https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/publication/saupe-middle-english-marian-lyrics), accessed August 11, 2020.

Sluhvosky, Moshe. Patroness of Paris: Rituals of Devotion in Early Modern France. Leiden, NL: Brill, 1998.

“Tableau-Reliquaire de Sainte Geneviève,” Musée de Cluny (https://www.Musée-moyenage.

fr/collection/oeuvre/reliquaire-sainte-genevieve.html), accessed August 10, 2020.

Notes

The author wishes to thank Dr. Elliott Wise for his suggestions and encouragement during the writing process.

[1] Genovefa in Latin and Sainte (abbreviated “Ste”) Geneviève in French is deaccented and anglicized as Saint Genevieve (abbreviated as the ungendered “St.”), as will be used here.

[2] Transubstantiation was officially accepted as Catholic doctrine by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.