21 December 2020 by bobhud

Saint or Sinner? Defining Women in Relation to the Satanic Serpent in Dürer’s Workshop

Lindsay Packham

Brigham Young University

Virgin or whore? Saint or Sinner? The Madonna-Whore dichotomy presents women as polarized extremes of the “good” pious virgin versus the “bad” promiscuous whore (“Madonna-Whore” 519).[1] While the term was first coined by Sigmund Freud to describe a heterosexual male complex, this misogynistic stereotyping of women appears in both Western and non-Western cultures in traditions that reach back to ancient Greece (Madonna-Whore 519). Since Freud, evolutionary psychologists have explained the Madonna-Whore dichotomy as stemming from a male fear that promiscuous women led to “paternity uncertainty,” resulting in men desiring faithful women as long-term partners to avoid caring for another man’s children (Madonna-Whore 520). Feminist theorists posit that the Madonna-Whore dichotomy reveals both benevolent and hostile sexism as it limits women by restricting them to either the, perceived, morally superior mother deserving of male protection, or the objectified woman who threatens men with her sexual agency (Madonna-Whore 520). In the Western Christian tradition, women—and female sexuality—have been blamed for the Fall of mankind since Eve’s interaction with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. This harsh stereotyping prescribes culturally appropriate sexual behavior for women and demonizes those who challenge this reinforcement of the patriarchy. Despite its prominence and endurance, the Madonna-Whore is a false dichotomy as women and their sexuality cannot be defined by these extreme, culturally constructed roles. Yet this deeply misogynistic tradition, reinforced through artistic representation, continues to force women into overly simplistic roles which reflect both benevolent and hostile sexism.

Consistent with this misogynistic tradition, representations of women in art have also been routinely restricted to the extremes of sanctity like the Virgin Mary or immorality like Eve. This distinction between saints and sinners appears in Northern Renaissance artworks created by Hans Springinklee and Hans Baldung Grien, both of whom were students of Albrecht Dürer. Springinklee’s woodcut of Saint Margaret of Antioch from 1518 (Fig. 1 below) portrays the saint as a righteous woman: following in the footsteps of the Virgin Mary as she stands above the conquered dragon.

Figure 1. Hans Springinklee, Saint Margaret of Antioch, 1518, 118 x 81 mm, The Illustrated Bartsch Vol. 12, Warburg Institute, University of London

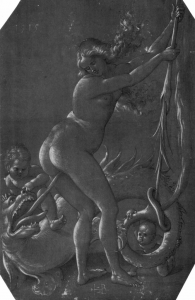

By conquering the Devil disguised as a dragon, Saint Margaret follows the biblical tradition of woman overcoming the Devil as God prophesied in Genesis 3:15, saying that the woman and her seed will have the power to bruise the serpent’s head. In stark contrast to this saintly representation by Springinklee, Hans Baldung Grien portrays female sin in his Witch and Dragon drawing from 1515 (Fig. 2):

Figure 2. Hans Baldung Grien, Witch and Dragon, 1515, pen and ink with white highlights on brown, prepared on paper, 29.5 x 20.7 cm. Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Kupterstichkabinett.

Witches were known as the “daughters of Eve,” as they were likewise enticed by the Devil into a fallen state (Owens, “The Saturnine History” 77). Baldung Grien, who pioneered the visual iconography of witches alongside Dürer, depicted the Devil disguised as a dragon participating in a graphic sex act with a witch. These artworks by Dürer’s students exhibit the Madonna-Whore dichotomy in which the “good” virginal woman defeats the Devil, while the “bad” sexualized woman is beguiled into a carnal relationship with him. Thus, the age-old dichotomy between the Virgin Mary and Eve appears again with Saint Margaret representing the saintly woman while the witch serves as an evil foil, a contrast illustrated by how these women interact with the serpent. The artistic illustration of their interaction with “that old serpent, called the Devil,” not only situates them at opposite ends of the moral dichotomy, but also presents these women as merely passive vessels for masculine powers: whether good or evil (Rev. 12:9).

Despite being polar opposites within the false Madonna-Whore dichotomy, these representations of women as saints or sinners share striking similarities. First, the categorization of these women as “good” or “bad” depends on how they interact with the masculine Devil, which, when shown as a dragon, is also a phallic symbol. There is a long history of the Devil, and his forms as serpent or dragon, being associated with “the obvious phallic connotations of the serpent’s body” (Tumanov 512). The phallic implication only serves to heighten the contrast between the chaste and the unchaste representation of Saint Margaret versus the witch. Second, both of these women are mere conduits for male power as God performs miracles through Saint Margaret, a virgin, while the Devil performs his mischief through witches and copulation with them. These representations of women have another notable difference. In addition to the obvious contrast in the representations of their sexuality, there also seems to be a contrast in how actively or passively the women are shown to be participating in the visualization of their narrative. In spite of Saint Margaret’s active role in defeating the dragon, Springinklee presents her as a stable, passive figure while Baldung Grien’s witch takes on a more active pose as she chooses to submit to or even spur the sexual advances of the dragon. The juxtaposition between the subjects as good or bad women is further supported by the contradicting roles of Saint Margaret as the patron saint of childbirth, and witches as murderers of children and assailants of fertility.

Springinklee’s woodcut Saint Margaret of Antioch conforms to traditional iconography of the saint as she is accompanied by a slain dragon, her most recognizable attribute. Two columns frame the saint, as she stands serenely with her left hand holding an elongated cross that pierces the dragon. Saint Margaret wears a slight smile and is adorned with a crown, denoting her status of noble birth. According to Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend written ca. 1260, Margaret was the daughter of a pagan patriarch, and she was baptized a Christian against her father’s wishes. When she was fifteen, the prefect Olybrius spotted her tending sheep and commanded a servant to, “Go and seize her! If she’s freeborn, I’ll make her my wife: if she’s a slave, she’ll be my concubine!” (Voragine 368). Upon declaring herself a Christian and unavailable for marriage, Margaret was imprisoned and tortured. Returning to her cell after torture, Margaret prayed to see her enemy and a ferocious dragon appeared. At this point in the narrative, the Golden Legend gives two accounts. The first states that when the dragon came to devour her, she made the sign of the cross and the monster disappeared. The author, Voragine, grudgingly describes a second version which has the dragon successfully devour Margaret, but the power of the cross gives her the ability to emerge from the belly of the beast unscathed. However, Voragine clarifies that this second account is “considered apocryphal” and is “not to be taken seriously” (369).

After this defeat, however it occurred, the Devil continues his attempt to beguile Margaret into submissiveness to him and turns into a human man. In response, she “pushed him to the ground, planted her right foot on his head, and said: ‘Lie still at last, proud demon, under the foot of a woman!’” (Voragine 369). Following this, the Devil lamented, “O blessed Margaret, I’m beaten! If I’d been beaten by a young man I wouldn’t mind, but by a tender girl…!” (Voragine 369). Saint Margaret’s legend culminates with her sentence to martyrdom by beheading. Before her imminent death, she prayed that “any woman who invoked her aid when faced with a difficult labor would give birth to a healthy child” (Voragine 370). Saint Margaret’s legend emphasizes her virginity, the power of God to overcome the Devil—even through a woman—and her connection to childbirth.

Baldung Grien’s Witch and Dragon drawing is less straightforward than the image of Saint Margaret, and scholars still actively debate possible interpretations of this artwork. The composition features a nude woman, with long unbound hair, twisting backwards to face a decidedly monstrous dragon in the bottom left corner. The witch holds a staff, or some kind of organic vine, which art historian Yvonne Owens describes as a “leafy, vegetal wand” (“Pollution and Desire” 346). The witch inserts this wand into the dragon’s tail, which emits a fiery blast. Two malicious putti figures clamber around the monster, who in turn contorts himself to face the witch: mouth agape and tongue extended. The element most debated by scholars is the connective stream between the witch’s legs and the dragon’s mouth. The substance itself is contested, as well as whether it originates with the witch or dragon. Linda Hults identifies this as the creature’s, perhaps second, tongue penetrating the witch, while Charles Zika suggests it could be fire originating from the dragon and directed towards the witch (Owens, “Pollution and Desire” 347). Yet, Katherina Siefert argues that it is the witch directing a stream of fire to the dragon as a sign of her growing power (Owens, “Pollution and Desire” 349). Owens offers yet another interpretation as she sees the stream as an “umbilical cord tissue” or menstrual blood, originating from the witch (Owens, “Pollution and Desire” 349). Whether the connective stream is a tongue, fire, or some sort of reproductive fluid, this aspect of the image seems to indicate some form of copulation between witch and demon. Regardless of interpretation, the key takeaway is that Baldung Grien presents this witch as an engaged sexual partner of the dragon.

While Owens and Siefert’s arguments are compelling, I am inclined to agree with scholars who think the substance originates from the dragon, as this reflects the witch’s subjugation to the Devil. The relationship between witches and the Devil was defined by sex, more specifically the witch’s lust which led to her submission to the Devil. Women, motivated by carnality, would seal their pact with the Devil through sexual intercourse (Hults 113). As Hans Broedel summarized, “the witch did not worship the devil, she slept with him” (163). It was generally believed that the lustful nature of these weaker women, led them to these unholy alliances. Witches, known for their “insatiable” sexual appetite, would “excite themselves with devils” to satisfy their lust (Broedel 159). This demonized women’s sexuality—presenting it as “inherently infernal” (Hults 114). Since women were considered to be more carnal than men, an active and assertive sex drive from a woman was thereby considered to be a primary identifier of a witch (Broedel 159). This embrace of sexuality separates the witch from saintly women who preserved their chastity either through abstinence or marriage. The dragon in Baldung Grien’s Witch and Dragon could be interpreted as a demon, or the Devil himself—either way it ultimately symbolizes the witch’s allegiance to the Devil. Thus, the witch demonstrates her deference to the Devil through submitting to a sexual relationship with this dragon.

Returning to the question of the power dynamic between Baldung Grien’s witch and dragon, it is possible to interpret the witch as being both an active and passive participant in the sexual encounter depicted. While it seems most likely that the connective stream emanates from dragon to witch—placing her in a passive or receptive position—the witch could also be engaging in a form of masturbation through the dragon. The witch penetrates the dragon’s tail with the vine, an action which could be prompting the dragon’s mysterious emission. If this is the case, the witch actively utilizes the dragon for her own pleasure. This explanation would unify the diagonals and twists of the composition by giving the eye a full visual loop to follow: from the distinct vertical vine, through the dragon’s twisting body, to the strong diagonal created by the dragon’s emission to the witch’s extended arms. This interpretation emphasizes the witch’s lustful nature by acknowledging her active participation in her own sexual experience, as well as her decision to submit to the Devil through the dragon’s advances. Thus, the witch is finding satisfaction for her lust, while also committing herself to a pact with the Devil.

As the early modern Renaissance began, the iconography of witches was just beginning to develop into codified stereotypes. Despite common misconceptions and the inclination to tie witches to the Middle Ages, the issue of witchcraft and witch-hunting is largely one of the early modern period. In fact, the height of the European witch hunt occurred during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Wiesner x). The chronology of witchcraft typically begins with the seminal work known as the Malleus Maleficarum (trans. The Hammer of Witches), written by Catholic clergymen Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, who published the treatise in Germany in 1487; this text molded the European conception of a witch by providing a detailed guide of identifying witches by how they looked and the perceived supernatural events surrounding them.

Unsurprisingly, this witch-hunting manual is full of misogynistic rhetoric. It presents women as more susceptible to witchcraft because they are the weaker, more lustful, and less rational sex. The Malleus Maleficarum unflinchingly states that the “greater number of witches is found in the fragile feminine sex than among men; it is indeed a fact that it were idle to contradict…” (I, 6). The manual assumes that the inferiority of women is a fact that needs little explanation. It also connects witches directly to Eve as, “All witchcraft comes from carnal lust which in women is insatiable. For although the Devil tempted Eve, yet Eve seduced Adam” (Tumanov 513). Kramer and Sprenger identify witches as having long wild hair, which symbolized their carnal nature. This sexist tradition accused the female body of inferiority, and consequently presumed that women were morally inferior as well. Many scholars concur that Dürer’s iconography drew directly from the Malleus Maleficarum, with Baldung Grien following suit (Neave 4). By basing his visual interpretation of witches on demonologist writings, Baldung Grien spread the “anti-female bias of the witch hunters” through his artwork (Neave 7). Thus, these artists developed the iconography of witches within an atmosphere of misogyny that specifically demonized female sexuality.

With this foundation of iconography and cultural context, it is possible to return to the first similarity between the image of Saint Margaret and the Witch and Dragon. The saint and witch are both defined by how they interact with the phallic symbol of the Devil. Phallic connotations of the serpent have a long history from “rabbinical sources” to Freud (Tumanov 512). In this instance, the saint is categorized as “good” for rejecting physical passion and maintaining her virginal status, while the witch is held in contempt for yielding to lust. Early versions of Saint Margaret’s legend excuse her violent attack against the Devil as necessary to preserve her chastity (Dresvina 194). Safeguarding her chastity was necessary to maintain her status as a religious woman in this life, and to become a bride of Christ in the life to come. Her inclusion among the Virgin Martyrs category of saints absolutely depended on this. Medieval Christians viewed the “repression of the body, in particular the female body,” as necessary “in order to glorify God” (Bledsoe 186). Saint Margaret succeeded in this repression and sacrificed her body to torture and death rather than a loss of virginity or renunciation of God. Saint Margaret’s virginity and chastity were the key to her “ultimate reward, a place in heaven as the sponsa Christi” (Bledsoe 192). Springinklee’s Saint Margaret illustrates her control over the Devil as she calmly subdues him with the cross. The dragon himself appears less threatening as he is depicted as more tame than menacing. This docility contrasts with Baldung Grien’s drawing where the dragon and witch contend against each other for dominance as they engage in mutual penetration. The composition of these artworks further highlights this contrast. Stabilizing horizontal and vertical lines dominate the image of Saint Margaret, whereas the image of the witch has a strong diagonal and therefore volatile focus.

The witch succumbs to the Devil and her lust, which medieval Christians would perceive as a particularly feminine moral failing. Witches were notorious for their insatiable sexual appetites, and rumors abounded that they sought out the Devil and his demons to satisfy these base urges (Broedel 159). Dragons, as an overt phallic symbol, offer artists an uncomplicated visual representation of the Devil’s sexual advances. While a saint, or nun, consecrating their virginity to God was an act of religious dedication, it was supposed that witches demonstrated their allegiance to the Devil through sexual relations with demons—also defined as a ritual act (Stephens 43). This ritual act of sexual submission demonstrated the witch’s “servitude, in both body and soul, to the demonic familiar to Satan” (Stephens 43). As such, these visual representations of Saint Margaret and a witch both signify their devotion to God and the Devil, respectively, as demonstrated through the saint’s virginity and the witch’s sexual indulgence. The morality of these women is determined by how they confront sexual temptation—with the virgin abstaining and the “whore” yielding. But ultimately, both women are defined by the nature of their relationship with the Devil and their response to sexual temptation.

The second similarity between Saint Margaret and the witch is that they both serve as conduits for male power, without any supernatural power attributed to either woman. In her legend, Saint Margaret defeats the Devil by calling on God through the sign of the cross. The Devil himself mentions his embarrassment at being overpowered by a “tender girl,” while Margaret humbly attributes the victory to God (Voragine 369). Margaret’s status as a woman, with the implication that this signified weakness, serves to further highlight the power of God, as he could successfully work through a fragile vessel. While Margaret imitates Christ’s passion, as she defeats the Devil through the cross, she cannot withstand these trials without divine intervention since she is “only human—and a woman at that” (Bledsoe 191). Springinklee’s depiction of a passive Margaret underscores her powerlessness. Thus, the artist captures Saint Margaret’s relative powerlessness as the true power is attributed to God. The witch, also considered to be without autonomous faculty, gained her delusion of power from the Devil. The concept of a powerful witch is complicated as she derived strength from the Devil, who was not supposed to be a match for God (Emison 629). The Malleus Maleficarum portrays women as dangerous, yet without possessing any power themselves (Briggs 263). Witches were believed to acquire the ability to inflict evil on society through a pact with the Devil—pacts believed to be consummated through sexual intercourse between witch and Devil, as imagined in this scene of the Witch and Dragon (Zika 26). In the early modern era, men often believed female power derived from female sexuality (Hults 100). So, women did not have power independently, but witches could acquire at least the illusion of power if she copulated with the Devil. Again, the saint and witch inhabit similar, yet directly opposite, roles as sexual conduits for either God or the Devil to further their objectives on earth. Whether virgin or whore, both are without independent sources of power.

The active and assertive Saint Margaret of legend does not appear in Springinklee’s woodcut. Instead, Springinklee depicts her as a passive, inactive figure. In her legend, Margaret aggressively takes down the Devil when he is in human form, placing her heel on his head. This action alludes to the biblical prophecy that through a woman, the serpent’s head will be bruised. This scripture is generally interpreted as referring to Christ, born of the Virgin Mary. By bringing the savior into the world, Mary repairs the damage placed on Eve: Ave replacing Eva. However, in this image the artist represented the assertive Margaret as a perfectly passive, static symbol of goodness and purity. This contradiction of narrative and representation demonstrates how as in legend God used Margaret as a conduit for his power, the artist uses her as an emblem and role-model for early modern Christians as she represents an unattainable, mythical perfection. Likewise, Baldung Grien’s Witch and Dragon has similar incongruities. The witch, surrendering to her own carnal nature and the sexual advances of the Devil, is portrayed in an active, potentially even masturbatory, pose. It seems ironic that the woman who the dragon conquers is given motion, whereas the woman who conquers the dragon appears motionless.

Springinklee’s Saint Margaret of Antioch and Baldung Grien’s Witch and Dragon represent opposing ends of the Madonna-Whore dichotomy—a division which ultimately acts as a patriarchal method of controlling women’s bodies, and their representation. Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth, exemplifies the late medieval and early modern “good” woman. She is the eternal virgin, while also being wife and mother by proxy as bride of Christ and protector of birth. Saint Margaret modeled virginity for nuns and offered lay women support during the dangers of childbirth (Bledsoe 189). Conversely, the witch exemplifies the “evil” woman, who indulges her sexuality outside of masculine control and threatens procreation. Witches jeopardized procreation by either directly harming children or preventing the possibility of a child. By committing infanticide, witches were the ultimate corruption of motherhood as they harmed rather than nurtured children (Roper 167). As such, witches embodied the antithesis of loving, saintly mothers by becoming the “antimother” (Purkiss 181). In addition to infanticide, witches directly harmed fertility as they were accused of causing men to be impotent and women to be barren (Briggs 267). So, witches were vilified for their sexuality and for the threat they posed to reproduction. These distinctions of good-versus-bad women, defined by their relationship to men and family, served to reinforce patriarchal control over reproduction, restricting women’s sexual behavior to two unrealistic extremes, dictated by men.

In conclusion, whether labelled a virgin or whore, either categorization is problematic as it perceives women through a construction that upholds patriarchal ideals. The Madonna-Whore dichotomy is founded upon misogynistic principles and equates women’s moral leanings with their sexuality. The women presented in these works not only share imposed morality in relation to the Satanic serpent, but also a dependence on receiving power from masculine sources. Thus, whether virgin or whore, both are subjected to unrealistic expectations imposed on them by a patriarchal system determined to regulate sex and reproduction.

Works Cited

Bareket, Orly, Rotem Kahalon, Nurit Shnabel, and Peter Glick. “The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy: Men Who Perceive Women’s Nurturance and Sexuality as Mutually Exclusive Endorse Patriarchy and Show Lower Relationship Satisfaction.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 79.9–10 (2018): 519–32.

Bledsoe, Jenny C. “The Cult of St. Margaret of Antioch at Tarrant Crawford: The Saint’s Didactic Body and Its Resonance for Religious Women.” Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures 39. 2 (2013): 173–206.

Briggs, Robin. “‘By the Strength of Fancie’: Witchcraft and the Early Modern Imagination.” Folklore 115.3 (2004): 259–72.

Broedel, Hans Peter. “The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft: Theology and Popular Belief.” In Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, ed. Merry E. Wiesner. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. 154–163.

Dresvina, Juliana. “The Significance of the Demonic Episode in the Legend of St. Margaret of Antioch.” Medium Ævum 81.2 (2012): 189–209.

Emison, Patricia. “Truth and Bizzarria in an Engraving of Lo stregozzo.” The Art Bulletin 81.4 (1999): 623–36.

Hults, Linda. “Dürer’s Four Witches Reconsidered.” Saints, Sinners, and Sisters: Gender and Northern Art in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Jane L. Carroll and Alison G. Stewart. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003. 95–126.

Kramer, Heinrich, and James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum, 1481. trans. Montague Summers, 1928. http://www.malleusmaleficarum.org/.

Neave, Dorinda. “The Witch in Early 16th-Century German Art.” Woman’s Art Journal 9.1 (1988): 3–9.

Owens, Yvonne. “Pollution and Desire in Hans Baldung Grien: The Abject, Erotic Spell of the Witch and Dragon.” In Images of Sex and Desire in Renaissance Art and Modern Historiography, eds. Angeliki Pollali and Berthold Hub. London: Routledge, 2017. 344–372.

Owens, Yvonne. “The Saturnine History of Jews and Witches.” Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural 3.1 (2014): 56–84.

Purkiss, Diane. “Women’s Stories of Witchcraft in Early Modern England: The House, the Body, the Child.” Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, ed. Merry E. Wiesner. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. 175–88.

Roper, Lyndal. “Witchcraft and Fantasy in Early Modern Germany.” Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, ed. Merry E. Wiesner. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. 163–175.

Stephens, Walter. “Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief.” Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, ed. Merry E. Wiesner. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. 41–49.

Tumanov, Vladimir. “Mary Versus Eve: Paternal Uncertainty and the Christian View of Women.” Neophilologus 95.4 (2011): 507–21.

Voragine, Jacobus de. The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Trans. William Granger Ryan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2012.

Wiesner, Merry E., ed. Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

Zika, Charles. “The Devil’s Hoodwink: Seeing and Believing in the World of Sixteenth-Century Witchcraft.” Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, ed. Merry E. Wiesner. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. 25–34.

Notes

[1] To establish the framework of the Madonna-Whore dichotomy, the next several quotes in this opening paragraph cite or paraphrase the article “The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy: Men Who Perceive Women’s Nurturance and Sexuality as Mutually Exclusive Endorse Patriarchy and Show Lower Relationship Satisfaction” by Orly Bareket, Rotem Kahalon, Nurit Shnabel, and Peter Glick (see biblio). To avoid repeating the four authors’ names, this work will be abbreviated parenthetically as “Madonna-Whore.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.